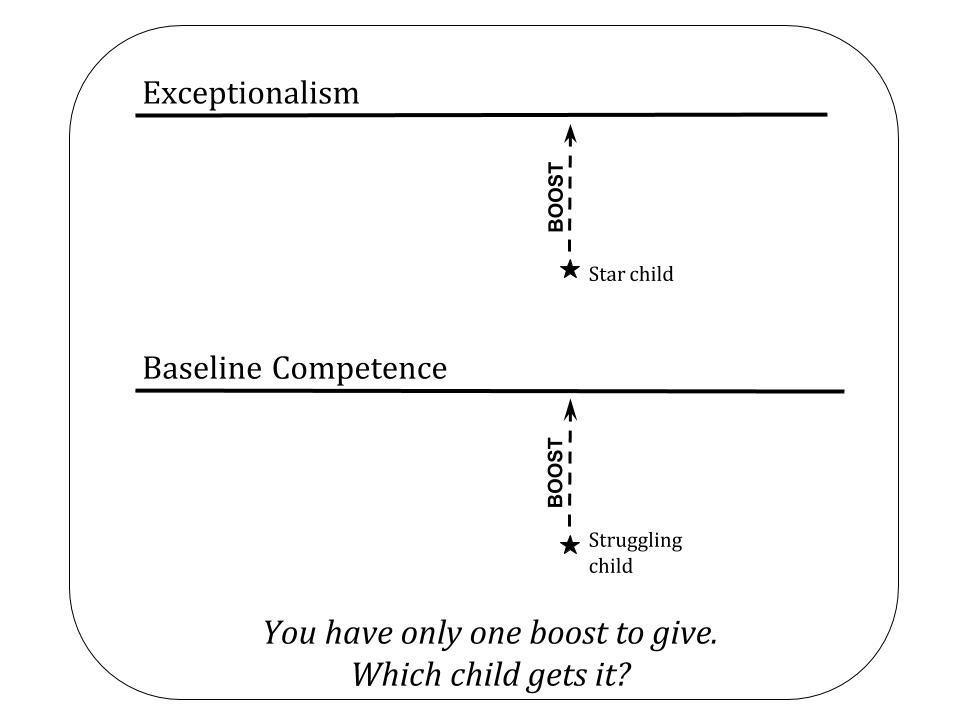

Suppose you have two children: One is a star. Bright, precocious, gifted in every way – clearly has a bright future ahead of them. The other is struggling. There are all sorts of challenges and difficulties hampering their ability to succeed. Now imagine that you have the resources to help only one of them. You cannot help both of them, you can only help one. Which do you choose to boost? Do you try to supercharge the precocious child to give them the best chance to catapult to the next level, or do you help the struggling child not fall behind their peers?

Maybe we can speculate that Isaac and Rebecca disagreed on how to navigate this quandary. They had twin boys, Jacob and Esav. Jacob was a star. He was studious and diligent and talented in every way, and certainly had a bright future ahead of him. Esav was a challenge. He had violent tendencies, he had promiscuous proclivities, he loathed studying, he was a loafer – he was at severe risk. Isaac had a blessing that he could give to only one of his sons. Isaac wanted to direct that blessing to Esav; Rebecca thought that Jacob deserved it. Perhaps their disagreement was that Isaac wanted to boost the weaker son, and Rebecca wanted to supercharge the stronger one. Ultimately, Rebecca subverted Isaac’s will and orchestrated a usurpation of the blessings.

In his own dealings with his descendants, Jacob followed Rebecca’s lead. In the end of Genesis, Joseph presents his two sons, Ephraim and Menashe, to Jacob to receive deathbed blessings. Despite Menashe being older, Jacob does a dramatic switcheroo, and crisscrosses his hands, and places his dominant right hand on Ephraim and his weaker left hand on Menashe. His reasoning: Ephraim deserved a stronger blessing because he is destined for a brighter future than Menashe. Again, with only one dominant blessing to offer, Jacob chooses to supercharge the more gifted in lieu of balancing things out – of creating equality – by lifting the weaker to parity with the stronger.

The greatest pedagogue of the 20th century, the Alter of Slabodka, R’ Nosson Tzvi Finkel, said that the sole purpose of his institution was to develop one prodigy, R’ Ahron Kotler, into a giant Torah scholar. Someone questioned him, “but your yeshiva has 400 other students. If R’ Kotler is the whole goal, your yeshiva could be much smaller!” The Alter responded, “R’ Kotler needs to study in the right kind of environment in order to flourish. And that’s why we need the 400 other students.” In the Alter’s eyes, creating an army of well-educated foot soldiers is not as important as creating the one general who can influence the masses.

Benjamin Franklin is a secular example of the impact a single person can have. One man can essentially found a republic, negotiate peace for that republic, invent the bifocals and lightning rods and all kinds of other things, and found a world-class university. It’s tempting to try to calculate how many ordinary citizens would you need to put on the other side of the scale to equal the accomplishments of one Benjamin Franklin.

I also think that the Jewish concept of Messiah fits in with this idea. We believe that a single transformational person will emerge who will succeed in getting the entire world to adjust its outlook and perspective. In effect, the idea of Messiah highlights the potential power of a single solitary person.

There is a pedagogical approach that argues that we ought to do whatever we can to create the next R’ Kotler, the next Benjamin Franklin, the next Steve Jobs, and who knows, maybe even the Messiah. Clearly, this is not the only legitimate approach to this dilemma. According to our insight, Isaac believed otherwise. As a parent, my instinct is to follow the Isaacian approach and to dedicate the lion’s share of my time and thought to the weaker children. But nevertheless I think the other side of the equation is definitely something worth pondering. There is an argument to be made that we should “put all our eggs in one basket”, we should go “all-in”, we should shoot for the stars with the best candidate for superstardom.